The recently launched Millennium Development Goals Report gives reason for optimism about achievement of the first goal: reduce extreme poverty by half. However, the figures do not display the little progress made for the poorest of the poor, those frequently excluded from poverty eradication programmes. A specific target is required in the post-2015 goals to make sure that no one will be ‘left behind’.

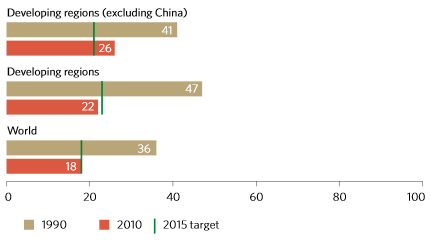

The recently launched preliminary figures on the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) show the success of particularly the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in eradicating poverty. The number of people living in extreme poverty has been reduced by 700 million since 2000: from 47 to 22 per cent of the developing world’s population and from 36 to 18 per cent of the entire world’s population.1 Similarly, the percentage of the world population living in hunger has decreased from 24 to 14 per cent. A large part of this success stems from UNDP youth and women’s employment programmes.

Figure 1: poverty eradication 2000-2010 (Source: MDG report 2014)

Although these figures give reason for optimism, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon stressed at the report’s presentation that “achievements have been uneven between goals, among and within regions and countries, and between population groups”. He continued by arguing that “our post-2015 objective must be to leave no one behind”.

However, ‘leaving no one behind’ requires more than continuing or even increasing UNDP’s efforts to reduce poverty. It implies giving priority attention to the people in the direst circumstances who are hardest to reach. Shortly before his death, Mahatma Gandhi wrote “recall the face of the poorest and weakest person you have seen, and ask if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to them”. Keeping Gandhi’s words in mind when dissecting the results of poverty reduction, we might have to temper our optimism.

Poverty within the pre- and post-2015 agenda

The first of the eight MDGs is to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, and is aimed particularly at those in dire need. This goal has been met even before the MDGs end (see figure 1 above). The MDGs’ successors, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), are currently taking shape. The UN Open Working Group, installed to design the SDGS, have presented their outcome document with a list of 17 proposed SDGs at their 13th and final session in July. According to the document poverty eradication is again the overarching goal of the SDGs: “poverty eradication is the greatest global challenge facing the world today and an indispensable requirement for sustainable development”.

Throughout the OWG negotiations, there has been consensus among member states about prioritising the goal of poverty eradication. The challenge has been to define exactly what poverty entails. The current goal in the outcome document is to “end poverty in all its elements everywhere”. The targets for this proposed goal are:

- by 2030, bring to zero the number of people living in extreme poverty, currently estimated at less than $1.25 a day in low income countries

- by 2030, reduce by at least half the proportion of people of all ages living below national poverty definitions

- by 2030, implement nationally appropriate social protection measures including floors, with a focus on coverage of the poor and people in vulnerable situations

- by 2030 secure equal access for all men and women, particularly those most in need, to basic services, the right to own land and property, productive resources and financial services, including microfinance

- by 2030 build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations to disasters, shocks and climate-related extreme events

Two things stand out in comparison to the MDGs. First, the goal is now to eradicate extreme poverty in its entirety. The logic underpinning this goal is that since poverty has been decreased by half in the past 15 years, the other half can be decreased in the upcoming 15 years. Second, in contrast to the MDGs, there is an emphasis on reducing poverty in all its elements. This builds on Ban Ki-Moon’s plea for a “strong successor framework to attend to unfinished business and address areas not covered by the eight MDGs”. In relation to the MDGs, there is also attention for social protection, services, land rights and resilience, as well as for including marginalised groups.

Exclusion and self-exclusion

The idea of ending extreme poverty by 2030 is based on linear reasoning. “Since we reduced poverty by half in the past 15 years, we’ll need only 15 more years to reduce the other half” could have been used as an argument during the OWG negotiations. However, this reasoning ignores how and why UNDP programmes work. As Nicky Pouw pointed out at the 2014 Woord en Daad annual conference, several groups of extremely poor people have not been reached by the development programmes, notably the ‘poorest of the poor’. Research by the African Studies Centre revealed that these groups want to be included but are aware they are consciously excluded.2

What, then, are the causes for this exclusion? First, the programmes have no incentive to reach out to the poorest of the poor. Development programmes under the MDGs are aimed at a more general target group, mostly because of the rigid standards used for measuring poverty. Applying a poverty line of $1.25 a day, for example, creates little incentive to target those living far below $1 a day. It is much easier, and therefore more attractive for those implementing the programmes, to target those who already have an income close to the poverty line. Microcredit programmes, for instance, have more incentive to target those who are able to repay their loans. And this applies not only to income: those who already have more social, financial and cognitive resources are more likely to be included within development programmes because they are more easily targeted.

Second, the definition of poverty used was limited. Pouw described how the poorest of the poor can only be reached if their poverty is seen not only in money-metric terms: their well-being needs to be taken into account as well. The definition of poverty should include social and cognitive/psychological elements of well-being since, apart from being excluded, the poorest often willingly exclude themselves from the programmes for social-psychological reasons (i.e. their relation to their social environment or their lack of confidence).

The incorporation of elements like social protection and land property within the outcome document can be considered an improvement, since it moves beyond the pure money-metric definition of poverty. However, this only solves the issue of how the poor are defined and which conditions need to be improved, but not how they should be targeted.

Including the excluded

If Ban Ki-Moon’s premise of leaving no one behind were to be the guiding principle of post-2015 development, specific programmes would be required to target the poorest of the poor. These groups are very diverse in both their socio-demographic composition and their psychological and cognitive capacities. Due to this complexity it is highly optimistic to expect as many poor people to be lifted out of poverty in the next 15 years as in the past 15.

The SDGs therefore need to include a specific, long-term target on incorporating the poorest of the poor: a target that devotes special attention to how to reach the poorest in society and how to design programmes to include them. These programmes should aim to include those in the informal economy, those without education and those living in the rural periphery in developing countries. Programmes need to take the social environments of their participants into account and should aim to understand and improve their psychological status. This understanding cannot be achieved by applying SMART targets,3 which are inflexible and would lead programmes to target the greater group rather than specifically focusing on those previously excluded. The target therefore requires stability, patience and an on-going process of reflection.

Footnotes

- Extreme poverty is defined under MDG1 as those having an income of less than $1.25 a day. This target was initially set at $1 per day.

- Commissioned by Woord en Daad, yet to be published. The conclusions are based on the ASC’s (unpublished) Synthesis Report on research conducted in Benin, Bangladesh and Ethiopia.

- SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.